Introduction

By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime

UN Sustainable Development Goals Target 16.4

Global agreement in 2015 on the Sustainable Development Goals framework, to guide worldwide progress in the period to 2030, includes for the first time a target to reduce illicit financial flows (IFF). But the challenge is this: without agreement on methodologies to measure the scale of IFF, how can the target be met? How, indeed, can it even be attempted, or monitored?

In this book we pull together the very sizeable literature that addresses one or more components of IFF, from academic authors and from international institutions and civil society organisations. Our aim is to provide a robust critique for each approach of the methodology and the data used, in order to provide two main outcomes. At the general level, we see the findings as a basis for reference for the many scholars and experts working in the field, for whom better numbers are always preferable but it’s not always possible to be knowledgeable in each and every area. At the specific level, we hope this book will also form a valuable input to the UN process to identify indicators and ultimately to make meaningful progress on SDG 16.4.

January 2018: As we publish online this draft of the first chapter of the volume, our intention is to initiate a process that will see a wide range of engaged researchers, activists and policy experts collaborate in critiquing and strengthening this work. We hope you will highlight missing works from our survey, challenge our evaluation and strengthen our conclusions. All contributions will be gratefully acknowledged when the book is eventually published in full, including as named co-authors on particular chapters where the contribution is substantial.

Contents

The intention in this volume is not to provide a comprehensive overview of estimates of every IFF component, nor of every IFF channel. We focus on the main areas of the literature – academic and beyond – in which rigorous, replicable methodologies have been developed. In general, we give priority to those approaches generating global estimates based on country-level findings. We also prioritise those estimates that have been most salient in policy discussions, and those which we find to be most robust – although these are, sadly, not always mutually reinforcing.

As a result of this approach, since estimates of illicit flows associated with illegal markets are generally made at the national level, and tend not to be widely replicated across countries, this literature is largely excluded from consideration. The estimates of undeclared assets held offshore will include much of the ultimate proceeds of these crimes, however. We also do not address the literature on national tax gaps. This is in part for the same reasons, and in part because tax gaps may be purely domestic rather than necessarily reflecting the cross-border transactions that characterise IFF.

We address four main areas of estimates. First, chapter 2 evaluates the literature on trade-based IFF. Separate sections address the literature using national-level data; that using commodity-level data; and that using transaction-level data. Chapter 3 focuses on estimates based on capital accounts anomalies, with separate sections addressing the approaches of Global Financial Integrity; of Ndikumana and Boyce; and of James Henry. A final section considers the estimates that combine trade-based and capital account components.

In chapter 4, we focus on the leading estimates of undeclared wealth held ‘offshore’ – specifically the approaches associated with James Henry and with Gabriel Zucman, respectively. Chapter 5 evaluates the much larger and more varied literature on the extent of multinational profit shifting – from international organisations including UNCTAD, the IMF and OECD, to key individual authors such as Kim Clausing. Chapter 6 is addressed to a range of alternate approaches. In particular, we examine risk-based proxy measures for IFF; and policy-based indicators for progress that could substitute or complement scale measures that seek to capture precise levels of currency movements.

Despite the major differences in composition, each chapter follows a consistent format to allow easy use for different readers. First, as noted, each section describes a particular methodology or methodology type. In each case, a separate treatment is given for the quality of the data and the quality of the methodology. These include assessments of the scope for improvement and/or the likelihood of access to better data. Each section, and each chapter, also include overview and conclusion sub-sections with key findings which can be read as standalone summaries.

Finally, chapter 7 presents the overall conclusions of the book and makes recommendations for the most promising directions for future research, and the most pressing and realistic priorities for data collation and data access. We highlight the most robust current estimates, and draw out the implications of our analysis for target 16.4 of the Sustainable Development Goals.

The remainder of this chapter explains the motivation for the book and addresses the key definitional questions and other issues that are common to all the material that follows, including a discussion of the associated development damage that justifies the important inclusion of illicit financial flows in the Sustainable Development Goals framework. We also take the opportunity to explain a number of decisions we have taken to limit the scope of the work that we evaluate; and to lay out the structure of the book, which is designed to provide straightforward, practical reference (the answers!) as well as detailed analysis (the reasons).

Context and motivation

The emergence of a global ‘tax justice’ movement, following the formal establishment of the Tax Justice Network in 2003, has had a powerful impact on international policymaking. By 2013, a range of innovative policy proposals had risen onto the agendas of the G8, G20 and OECD groups of countries. And by 2015, the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) themselves had come to embody that shift also.

Most obviously, tax appears as the first ‘means of implementation’ in the SDGs (target 17.1). This stands in stark contrast to the predecessor framework, the Millennium Development Goals, which contained no single reference to tax as a source of finance for development. In addition, the closely related issue of

illicit financial flows has also gained major policy traction.

The illicit flows agenda emerged in a fair degree as an opposition to a view which saw corruption as a problem largely, or even exclusively, of lower-income countries. Raymond Baker, the US businessman who worked for decades in sub-Saharan Africa before setting up the NGO Global Financial Integrity, popularised the term ‘illicit financial flows’ in his 2005 book, Capitalism’s Achilles Heel. The key selling point of the book was Baker’s ballpark estimates of the scale of flows, with ‘commercial tax evasion’ many times larger than flows linked to the bribery of, and theft by, public officials.

Baker’s first chapter is starkly titled ‘Global capitalism: Savior or predator?’, and the emphasis is clear from the first paragraph (p.11):

“I’m not trying to make a profit!” This rocks me back on my heels. It’s 1962, and I have recently taken over management of an enterprise in Nigeria. The director of the John Holt Trading Company, a British-owned firm active since the 1800s, is enlightening me about how his company does business in Africa. When I ask how he prices his imported cars, building materials and consumer goods, he adds, “Pricing’s not a problem. I’m just trying to generate high turnover.”

Baker goes on to lay out powerfully how the abusive behavior of multinationals of the period led to massive trade mispricing, and stripped lower-income host countries of their taxing rights – despite the often desperate need for revenues to support public spending on health, education and infrastructure. For the same reason, a key plank of the Tax Justice Network’s policy platform is the proposal for public, country-by-country reporting by multinationals (Murphy 2003) to lay bare the discrepancies between where economic activity takes place and where taxable profits are declared.

Illicit financial flows encompasses much more than multinational tax abuses, however. The opacity of corporate accounts that hides profit shifting finds a parallel in the financial secrecy offered by ‘tax haven’ jurisdictions – and this, too, is a critical driver of illicit flows.

In 2007, the Tax Justice Network began the process to create the Financial Secrecy Index, which identifies major financial jurisdictions like Switzerland – which typically does very well in international perceptions of corruption – as central to the problem of producing and promoting corrupt flows elsewhere (see Cobham, Janský, & Meinzer (2015)). A narrative that sees corruption in lower-income countries only will miss this central driver of the problem – and so an important element of the illicit flows agenda is that recognises the centrality of financial secrecy in particular, often high-income jurisdictions, to the undermining of revenues, the undermining of good governance in countries all around the world. Rather than saying ‘Why is your country corrupt?’, it says, ‘What are the drivers of corruption – and where?’

Underpinning every major case of corruption around the world, and many major cases of tax abuse, can be found anonymously owned companies, from the British Virgin Islands to Delaware; opaque corporate accounting, typically in the biggest stock markets in the world, that cover the degree of profit-shifting and tax avoidance; and deliberate failures to exchange financial information that protect, even now, banking secrecy.

As such, international cooperation is needed – at least as much as domestically focused efforts. The global agreement on a target (16.4) in the SDGs committed to the reduction of illicit financial flows (IFF) is therefore particularly significant. Politically, the target can be traced back to the work of the High Level Panel on IFF out of Africa, chaired by former South African president Thabo Mbeki, which worked with the UN Economic Commission for Africa to build the case for urgent action both on the continent and globally, and obtained unanimous African Union backing. It was natural that the subsequent report of the Secretary-General’s High Level Panel of Eminent Persons on the Post-2015 Development Agenda, co-chaired by President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono of Indonesia, President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, and Prime Minister David Cameron of the United Kingdom, also clearly identified IFF as an issue to be included in the new framework.

Despite this broad backing, however, the IFF target has proven to be one of the most difficult to pin down. Even now in 2018, there is no specific indicator or group of indicators agreed as the basis to track progress. Worse, there has been a concerted effort to subvert the target by removing multinational companies from the scope, despite the consistent emphasis on their tax avoidance practices in the academic and policy literature and in the reports of the two high level panels that set the basis for global agreement on the target in 2015.

With UNCTAD and the UNODC now leading a technical expert process to agree proposals, for agreement in 2018, there is the potential – but not yet the certainty – of ensuring the target has indicators which both reflect the original policy intention, and also create appropriate accountability mechanisms to support genuine progress.

The current indicator title is this:

16.4.1 Total value of inward and outward illicit financial flows (in current USD)

Setting aside whether such an indicator is most suitable to support progress and accountability, or sufficient on its own, the process to identify a methodology for this indicator is severely complicated by the absence of agreement on how to measure the scale of illicit financial flows. A specific aim of this book is to provide a basis for rigorous comparison of current approaches to estimating IFF, that can support national and international policymaking and global accountability for progress towards SDG 16.4.

Our more general motivation is to provide a reference tool for scholars, students, activists and journalists. ‘Illicit financial flows’ is an umbrella term for a broad group of cross-border economic and financial transactions, each of which have different motivations and a range of varying impacts. For activists and journalists, for example, this makes it important to distinguish when estimates refer to one IFF component or another, for example, as well as to have a robust basis for preferring one estimate over another. For researchers and experts in one area of IFF, who will not necessarily be as familiar with issues related to another component, an up-to-date guide to methodological and data questions should have clear, practical value.

Definitions

There is no single, agreed definition of illicit financial flows (IFF). This is, in large part, due to the breadth of the term ‘illicit’. The (Oxford) dictionary definition is: “forbidden by law, rules or custom.” The first three words alone would define ‘illegal’, and this highlights an important feature of any definition: illicit financial flows are not necessarily illegal. Flows forbidden by “rules or custom” may encompass those which are socially and/or morally unacceptable, and not necessarily legally so.

This is in line with developments in criminology, which has seen a growing zemiological critique (e.g. Hillyard & Tombs (2004) and Dorling et al. (2008); zemiology being the study of social harms). The critique emphasises a range of shortcomings in the crime-led approach, among them that crime is a social construct based on value judgements and so varies across time and geography – thereby undermining it as a consistent basis of comparison; and that crime as a category excludes many serious harms (e.g. poverty or pollution). A related point, first raised by Blankenburg & Khan (2012), is that a legally-based definition requires a legitimate state actor. Cross-border flows could be declared illegal by an illegitimate state (a military dictatorship, say). But would they therefore be illicit? As such, working on the basis of harm done (or risk thereof) can provide a more consistent basis for the definition.

To take a specific example, commercial tax evasion affecting a low-income country where the tax and authorities have limited administrative capacity is much less likely to be either uncovered or successfully challenged in a court of law, than would be the same exact behaviour in a high-income country with relatively empowered authorities. A strictly legal definition of IFF is therefore likely to result in systematically – and wrongly – understating the scale of the problem in lower-income, lower-capacity states. In contrast, a zemiological approach would clearly support the inclusion of multinational profit shifting since the revenue impacts and related harms in the grey area of ‘possibly legal but untested’ avoidance are indistinguishable from those which are firmly in the ‘unlawful’ category.

For these reasons, a narrow, legalistic definition of IFF is rejected. The phenomenon with which we are concerned is one of hidden, cross-border flows, where either the illicit origin of capital or the illicit nature of transactions undertaken is deliberately obscured.

The most well-known classification stems from Baker (2005). In Baker’s assessment, there were three components: grand corruption accounted for just a few per cent of illicit flows; laundering of the proceeds of crime between a quarter and a third; and the largest component by far was ‘commercial tax evasion’, through the manipulation of trade prices, accounting for around two thirds of the problem.

A somewhat extended classification, from Cobham (2014), identifies four components of IFF, distinguished by motivation: 1 - market/regulatory abuse, 2 - tax abuse, 3 - abuse of power, including the theft of state funds and assets, and 4 - proceeds of crime. The third and fourth components map onto two of Baker’s. The tax abuse category makes explicit an issue that is sometimes obscured in presentation of Baker’s categorisation, namely that tax-motivated IFF include not only the actions of multinational companies but also those of individuals. The first category, of market/regulatory abuse, is largely additional to Baker’s categorisation. These IFF reflect cross-border flows in which ownership is hidden, for example to circumvent sanctions or anti-trust laws. Circumvention of (legal or social) limitations on political conflicts of interest may fall here or under abuse of power.

This categorisation allows in turn the identification of the major actors in IFF:

• private actors (individuals, domestic businesses and multinational company groups committing tax and regulatory abuse, and the related professional advisers – tax, legal and accounting) – these are the leading actors in IFF types 1, 2 and 3;

• public officeholders (both elected and employed) – these are important actors in IFF types 3 and 4, and may be involved in type 1; and

• criminal groups (a term used here to indicate both those motivated primarily by the proceeds of crime, and those using crime to fund political and social agenda) – the leading actors in IFF type 4.

Table 1 provides an overview of the underlying transaction types. It is unlikely to be comprehensive because there is potential to engineer an illicit flow in any transaction, and the range of potential illicit motivations is wide indeed; but nonetheless demonstrates the breadth of IFF phenomena. As the final two columns indicate, all four IFF types are likely to result in reductions in both state funds and institutional strength – that is, both in the funds available for public spending and in the likely quality of that spending.

There is substantial overlap in the mechanisms used for IFF, regardless of motivation. The opportunity to hide, where it exists, is likely to be exploited for multiple purposes. For example then, the legal use by a multinational of highly secretive jurisdictions may both provide cover for illegal use of the same secrecy, and also inadvertently legitimize such behaviour. Identifying illicit flows in a particular mechanism will tend to be insufficient to specify the type of IFF in action.

Table 1 shows a roughly equal number of potential IFF in each of the first three categories, and rather fewer for the proceeds of crime; but this rests on an assumption made for descriptive clarity which is unlikely to hold in practice: namely, that businesses operating internationally are not used to launder the proceeds of crime. This distinction in turns highlights a more important one: namely, that IFF can take place with capital which is anywhere on a spectrum of legality. At one end are criminal proceeds and stolen public funds, with legitimate income and company profits at the other.

A second spectrum exists in relation not to the capital but rather the transaction itself. At one end there are clearly illegal transactions, such as bribery of public officials by commercial interests; at the other end, transactions which are likely to be legal (at least in the sense of not having been challenged successfully in a court of law) but may well be illicit; in this category would be, for example, some of the more aggressive transfer pricing behaviour of multinational companies.

Figure 1 provides a rough plotting of the four IFF types identified, on a quadrant diagram showing the spectra of transaction licitness and capital legality. The historical emphasis of both research and policy has been on those IFF types that are furthest, in general, to the northeast quadrant (i.e. where both the capital origin and the transaction are in question); and least attention to those in southeast (i.e. those where the capital origin is less likely to be in question than the manipulations involved in the transaction.

Most attention, in other words, has been paid to the clusters relating to abuse of power, and more recently to the proceeds of crime – at least in relation to efforts against ‘terrorism financing’ subsequent to the World Trade Center attacks of September 2001. The areas of market abuse and tax abuse have been relatively neglected in terms of policy focus, with the result that the dominant discourse has largely excluded the role of private sector actors in driving illicit flows – at least until the financial crisis affecting many countries that began in 2008.

Table 1: A typology of illicit financial flows and immediate impacts

| Flow | Manipulation | Illicit motivation | IFF type | Impact on state funds | Impact on state effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | Over-pricing | Exploit subsidy regime | 2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| (Re)patriate undeclared capital | 1 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Under-pricing | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Shift criminal proceeds out | 4 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Evade capital controls (including on profit repatriation) | 1 | ↓ | |||

| Imports | Under-pricing | Evade tariffs | 2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| (Re)patriate undeclared capital | 1 | ? | ↓ | ||

| Over-pricing | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | ↓ | |

| Shift criminal proceeds out | 4 | ? | ↓ | ||

| Evade capital controls (including on profit repatriation) | 1 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Inward investment | Under-pricing | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Shift criminal proceeds out | 4 | ? | ↓ | ||

| Evade capital controls (including on profit repatriation) | 1 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Over-pricing | (Re)patriate undeclared capital | 1 | ? | ↓ | |

| Anonymity | Hide market dominance | 1 | ↓ | ||

| Anonymity | Hide political involvement | 3 | ↓ | ||

| Outward investment | Under-pricing | Evade capital controls (including on profit repatriation) | 1 | ↓ | |

| Over-pricing | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ? | ↓ | |

| Shift criminal proceeds out | 4 | ↓ | ↓ | ||

| Anonymity | Hide political involvement | 3 | ↓ | ||

| Public lending | (If no expectation of repayment, or if under-priced) | Public asset theft (illegitimate allocation of state funds) | 3 | ↓ | |

| Public borrowing | (If state illegitimate, or if over-priced) | Public asset theft (illegitimate creation of state liabilities) | 3 | ↓ | |

| Related party lending | Under-priced | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | |

| Related party borrowing | Over-priced | Shift undeclared (licit) income/profit | 2 | ↓ | |

| Public asset sales | Under-pricing | Public asset theft | 3 | ↓ | |

| Anonymity | Hide market dominance | 1 | ↓ | ||

| Anonymity | Hide political involvement | 3 | ↓ | ||

| Public contracts | Over-pricing | Public asset theft | 3 | ↓ | |

| Anonymity | Hide market dominance | 1 | ↓ | ||

| Anonymity | Hide political involvement | 3 | ↓ | ||

| Offshore ownership transfer | Anonymity | Corrupt payments | 3 | ↓ | ↓ |

Source: Cobham (2014). ‘IFF type’ is defined as follows: 1 – market/regulatory abuse, 2 - tax abuse, 3 – abuse of power, including theft of state funds, 4 – proceeds of crime.

Table 2: A simpler outline of illicit financial flows

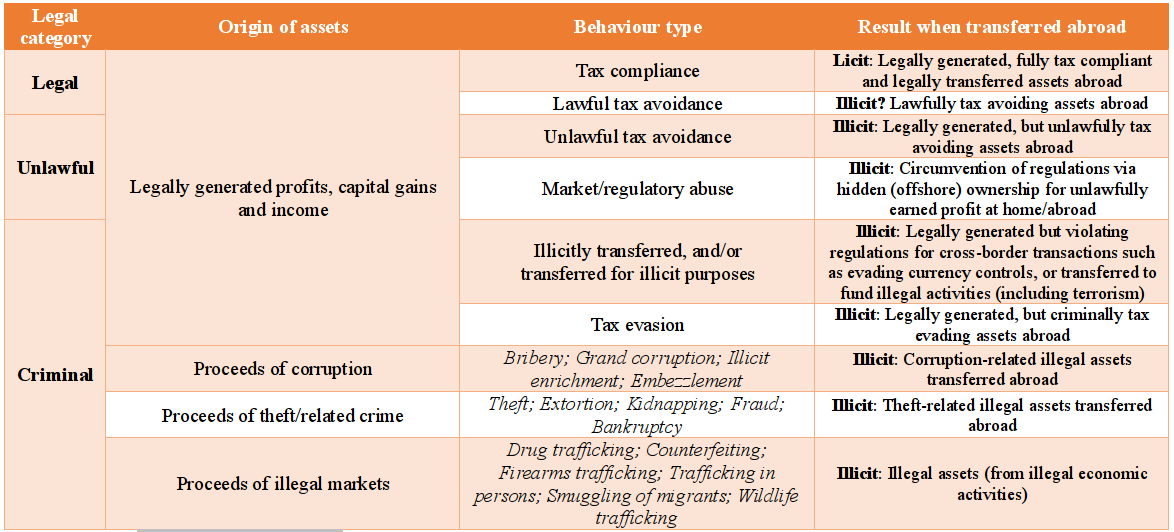

Source: Cobham and Jansky (2017b),building on earlier outline by UNODC, from which text in italics is drawn.

Source: Cobham and Jansky (2017b),building on earlier outline by UNODC, from which text in italics is drawn.

Figure 1: Main IFF types by nature of capital and transaction

It is worth reiterating that in all cases in the typology, the behaviours in question are in some sense reprehensible. They rely on being hidden because there would be substantial negative ramifications to their becoming publicly visible. These ramifications might be legal or social – that is, they may reflect violations of law or of ‘rules and custom’ – and in each case are sufficiently powerful to justify any costs of hiding. As such, it is inevitable that estimates of these deliberately hidden phenomena exhibit a degree of uncertainty. Moreover, since different IFF types use the same channels, estimates of particular channels will inevitably combine some IFF types to some degree; and since different IFF types use multiple channels, ‘clean’ estimates of individual IFF types may be difficult to obtain.

Finally in this section, we explore further the nature of multinational companies’ tax abuses and the extent of their inclusion in the definition of IFF. As noted, Raymond Baker’s original work took all of the profit shifting behaviour observed – not unreasonably – to be illegal tax evasion. This allowed the NGO that Baker established, Global Financial Integrity, to include his approach in a definition of IFF requiring strict illegality of capital or its transfer. However, it is clear in inspection of Baker’s analysis that much that has been labelled multinational tax avoidance by others would be included. Prof. Sol Picciotto has highlighted that there are in fact three categories to consider, rather than two: instead of looking at illegal evasion and legal avoidance, policy should identify illegal evasion; unlawful avoidance; and lawful (successful) avoidance, while recognising that there are likely to be grey areas between each.

Table 2, developed as part of the UN process to agree indicators for SDG 16.4, clarifies illicit assets as the key outcome of each illicit flow – and distinguishes types of tax avoidance following Picciotto’s proposal. Since each illicit asset type is associated with harms ranging from the underlying loss of public assets, promotion of criminal activities and tax losses, this simpler approach may be less helpful for specific policy responses. It does however offer a broader framing which may prove helpful in allowing simpler, harm-relevant indicators to be constructed.

Picciotto’s three categories make up the various forms of profit shifting, which must be distinguished from profit misalignment. Misalignment is a broader term that has gained currency since 2013, when the G20 and OECD declared that the single goal of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Action Plan (BEPS) was to better align taxable profits with the location of multinationals’ real economic activity. Profit misalignment can occur due to any of the three categories of profit shifting activity intended to reduce companies’ tax liabilities, and also from a fourth category: misalignment that arises simply from the fact that OECD tax rules do not explicitly seek alignment, and therefore some divergence from full alignment would be expected even in the absence of tax-motivated shifting.

In addition, differences in governments’ willingness to pursue their full tax base will give rise to misalignment that does not result from attempts to procure profit shifting from elsewhere. Furthermore, there are natural differences in profitability, such as different capabilities of employees, that are independent of profit shifting, but which it may not be possible to isolate from profit shifting. Figure 2 shows the resulting distinctions between profit misalignment; profit shifting illicit financial flows; and non-legal profit shifting (the figure is for conceptual discussion only – it does not provide scale estimates of its various parts).

Figure 2: Multinational tax behaviour and IFFs

The broader definition of IFF, reflecting harm rather than strict legality, is also clearly reflected in the key UN documents that precede the global, political agreement on the Sustainable Development Goals – in particular, multinational tax avoidance is repeatedly identified in the pivotal report of the UNECA High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows out of Africa, and subsequently in the report of the High Level Panel of Eminent Persons to the UN Secretary-General.

A final, pragmatic reason to include multinational tax abuses within the scope of IFF is simply that the estimates may be of notably higher quality than for some other aspects.

Impact

One of reasons to pursue better estimates of illicit financial flows is to support, in turn, a better understanding of the scale and nature of their impacts across a range of aspects of human development. These impacts, like the phenomena themselves, many and varied. Figure 3 provides one stylisation of these, distinguishing between IFF that rely on illegal and on legal capital respectively.

Illegal capital IFF, in general, are seen as providing the greatest threat to negative security: that is, the ability of states to prevent, or to negate, insecurity at the personal, community, environmental and political levels: more specifically, the ability and willingness of states to act to reduce the risk of violence against the person, the risk of insecurity due to tensions between groups, the risk of environmental degradation and the risk of political rights violations. The state can be increasingly undermined by the growing role of criminal activity, including the trafficking of drugs, people and illegal goods from e.g. logging, fishing and mining, which may come to require or rely on the support of some state functions such as the military or customs agents; and also by the growth of crimes directly against the state, namely bribery to subvert state power for private gain (typically of multinational companies), and the effective theft by people in positions of power of state assets (or per table 1, the creation of illegitimate state liabilities).

Figure 3: Overview of IFF and human security linkages

Source: Cobham (2014).

As figure 4 illustrates, illegal capital IFF can give rise to a vicious cycle of negative insecurity, in which the growth of IFF further undermines the state’s legitimacy and/or fuels internal conflict; weakening in turn the state’s will or ability to act against IFF, and so increasing the returns to the underlying activity and the incentives to take part.

Legal capital IFF are seen as forming a similar vicious cycle with respect to positive security – that is, the ability of states to provide, to positively construct, secure conditions in which rapid human development can take place. This relates to economic opportunity and freedom from extreme economic inequality; and to the security of basic human development outcomes related to health and nutrition.

Figure 4: The vicious cycle of negative insecurity and illegal capital IFF

Source: Cobham (2014)

Tax is fundamental to the emergence of a State which is both able and willing to support the progressive realisation of human rights – and the relationships here go far beyond revenue. The 4Rs of tax (Cobham, 2005; 2007) provide a simple framework to consider these. Revenue is clearly crucial to States’ ability to provide public services from effective administration and the rule of law to health, education and infrastructure; as redistribution is crucial to contain or eradicate both horizontal and vertical inequalities. Less obvious may be the role of taxation in re-pricing – ensuring that the true public costs and benefits of social goods (like education) and ills (such as tobacco consumption and carbon dioxide emission) are reflected in market prices.

Perhaps the most important result of tax, however, is also often overlooked: political representation. Prolonged reliance on revenues from natural resources or foreign aid tends to undermine channels of responsive government, giving rise to corruption and broader failures of accountability. The act of paying tax provides an important accountability link (Brautigam et al. 2008; Broms 2011). Empirical studies suggest the higher the share of tax in government spending, the stronger the process of improving governance and representation (Ross, 2004; and powerfully confirmed with much stronger data by Prichard, 2015); while direct tax – taxes on income, profits and capital gains – appears to play a particularly strong role (Mahon 2005).

Figure 5 shows the potential vicious cycle that could arise with respect to legal capital IFF and positive (in)security. If the starting point is taken as an increase in legal capital IFF, the risks are of undermining both the available revenues to provide positive security, but also the political responsiveness to be willing to do so. The resulting insecurity and inequalities have the potential to further weaken both the capacity and the willingness of the state to fight IFF, reinforcing the cycle.

Figure 5: The vicious cycle of positive security and legal capital IFF

Source: Cobham (2014)

Work on health impacts in particular has indicated potentially very powerful effects of IFF. Christian Aid (2008) began the current wave of tax justice campaigning by international development NGOs with an estimate that revenue losses due to trade-based tax abuse could result in the needless deaths of nearly 1,000 children each day. More recently, O’Hare, Makuta, Bar-Zeev, Chiwaula, & Cobham (2014) use illicit flow estimates with GDP elasticities of mortality to show that of 34 sub-Saharan African countries, a curtailment of illicit flows could see substantial mortality reductions – such that 16 countries rather than 6 would have reached their MDG target by 2015.

Reeves et al. (2015) explore the underlying relationship and find that "tax revenue was a major statistical determinant of progress towards universal health coverage" in lower-income countries, and that this is overwhelmingly driven by direct taxes on profits, income and capital gains. Using alternative revenue data, and a more robust regression approach, Carter & Cobham (2016) confirm the importance of tax generally, while adding some caveats and more detailed findings. In particular, they find a larger statistical association between direct taxes and public health expenditure than between indirect taxes and health spending; and that countries making greater use of direct taxes tend in general to exhibit higher public health spending, broader coverage of and access to public health systems.

A growing body of work has looked at the relationship between IFF and inequality. Income and wealth inequality are increasingly recognised as an obstacle to economic growth as well as to human development (e.g. Ostry, Berg, & Tsangarides, 2014; Piketty, 2014), and explicitly targeted and tracked throughout the Sustainable Development Goals framework. Cobham, Davis, Ibrahim, & Sumner (2016) show that allowing for IFF could be sufficient in many countries to require an upward adjustment to recorded income inequality of the same order as that required in adjusting top incomes for income reporting held by tax authorities (but systematically not provided in response to the household surveys on which most income distribution data is based) – perhaps 5 points on the Gini coefficient. Alstadsaeter, Johannesen, & Zucman (2017) use leaked data to show how strongly tax evasion in Scandinavia is concentrated in the top 0.01% of the wealth distribution; and hence how understated inequality will be if estimates rest on household surveys and tax reporting data alone. The ability of elites to opt out of direct taxation – whether as individuals or as major companies – not only undermines the redistribution possible through given tax policies, but also contributes with lobbying to reduce the attractiveness of pursuing redistribution. In the case of corporate taxation, multinational profit shifting creates an artificial disadvantage for smaller, national businesses – which are typically responsible for the majority of employment in a country.

Illicit financial flows have, therefore, tremendous power to cause damage to states, economies and societies. The extent of that damage depends ultimately on the scale of IFF themselves. The aims of this volume include supporting the selection of better estimates for future work on impacts; and supporting efficient prioritisation of approaches and data likely to lead to better estimates.